I was in Blackpool late September 2022 for a concert and I didn’t have a clue about the place. A Mancunian friend said it was one of those seaside resorts that had its heyday in the postwar decade (when it received 17 million visitors a year) but that it now was the perfect embodiment of Everyday Is Like Sunday’s line ”this is the coastal town that they forgot to close down”.

A glance on the Blackpool Wikipedia article says the town grew into a popular destination for the working class in the mid-19th century when Lancashire cotton mill owners took turns to shut down their factories for maintenance one week per year which provided a steady stream of visitors to Blackpool. Famous for its promenade, piers and perhaps especially its electrical lights – it was the first municipality in the world (1879) to have electric street lighting and its electrical tramway (1885) is also one of the world’s first. The (according to British friends apparently very famous) Blackpool Tower, inspired by the Parisian Eiffel Tower, was opened in 1894 and was at the time the tallest man made structure in the British empire.

- Photochrom of the Blackpool promenade, from Wikipedia (public domain).

- Blackpool Tower in September 2022.

The increased popularity of package holidays abroad meant Blackpool lost its traditional tourist crowd and as I understand it’s now mainly day tourists who go there, and not nearly as many as before. However, tourism remains a pillar in the town’s economy. A fun fact is that Blackpool shares its etymology with Dublin on the other side of the Irish sea: Dublin is derived from Irish Duibhlinn which means ”black pool” (though the common name for the city in modern Irish is Baile Átha Cliath, ”town of the hurdled ford”).

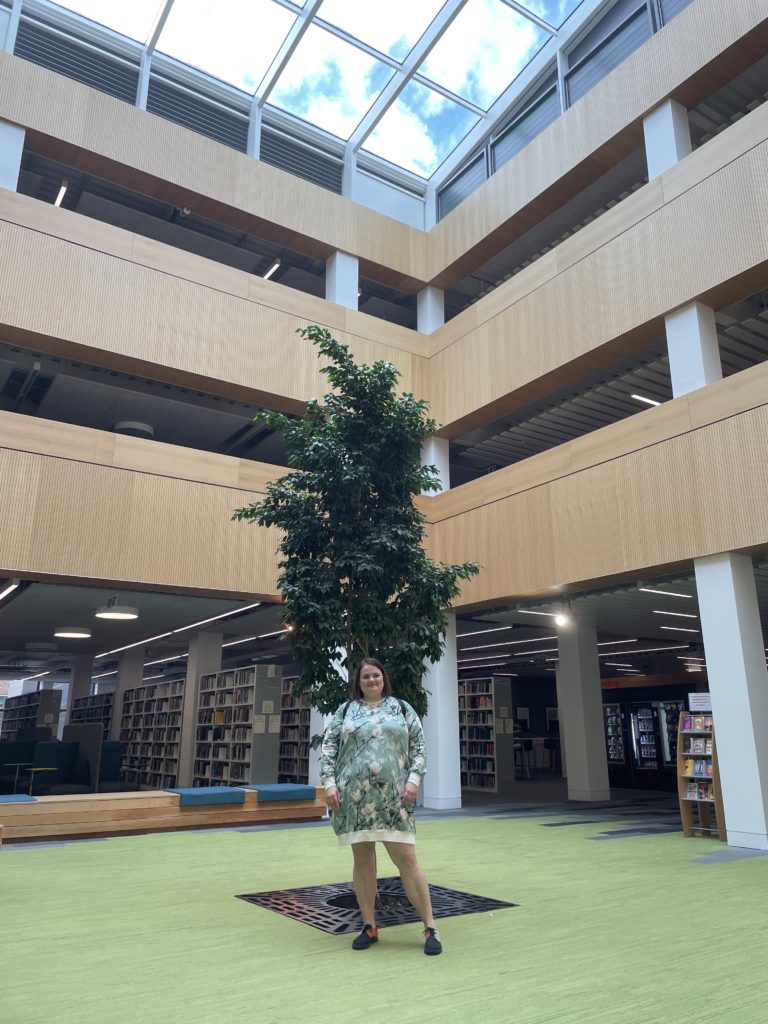

- Blackpool Central Library.

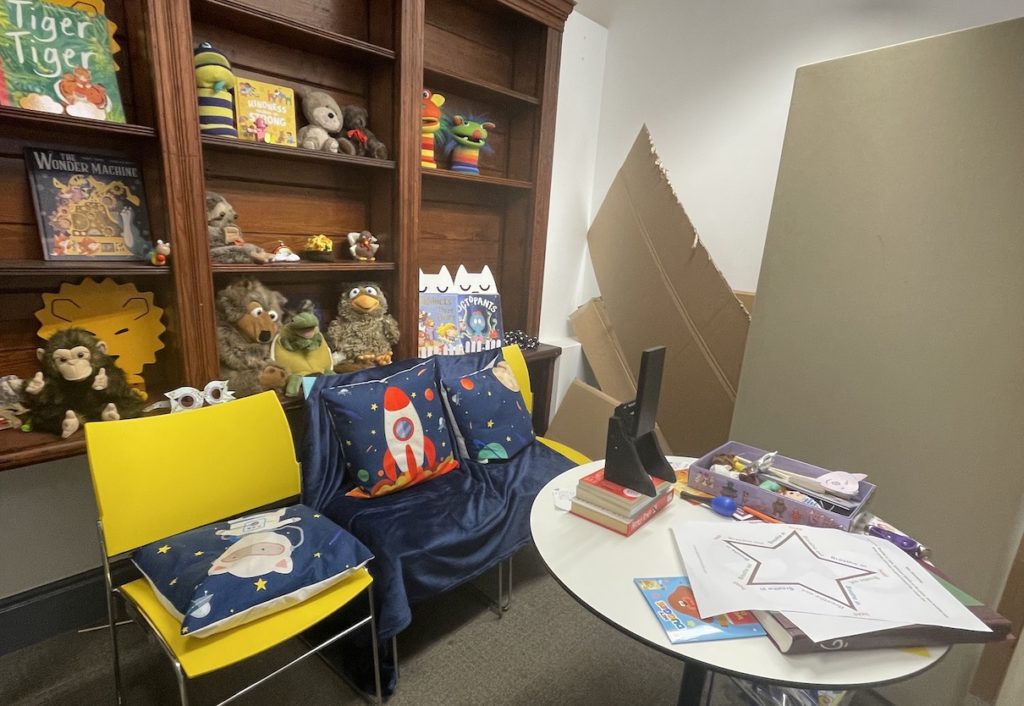

- Children’s section at Blackpool Central Library.

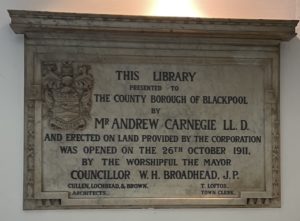

Knowing a bit about Blackpool’s history, it’s not surprising that it’s also home to a Carnegie library which serves as the main public library of the town. The Carnegie libraries were built between 1883 and 1929 with money donated from the Scottish-American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie and of the 2509 libraries, 660 are located in the United Kingdom and Ireland. What makes the Blackpool Central Library unique among Carnegie libraries is that it has a portrait of the philanthropist. As you ascend the stairs and reach the upper floor (which hosts local history collections and the Brunswick room) the donor’s gaze meet you from a stained glass window. This part of the library was closed of for renovation when I visited but the lovely librarian Jools showed me the closed section and also told me the story about the rare Carnegie portrait.

- Library saint in a stained glass window.

- Second floor of Blackpool Central Library.

- Carnegie donor’s plaque in the Blackpool Central Library entrance.

The public libraries of Blackpool have seven other branches that together with the Central Library serves the town’s population (~141,000 people). What really struck me with the Central Library was that it was so colourful. Many Carnegie libraries (and other libraries from the same era) I’ve visited look very similar, with white walls and an old fashioned sense of a library space trying to fit in with modern services. It’s hard to put my finger on it but I think it has something to do with only shelves, furniture, and signage dividing the space into different sections, whereas in Blackpool painted walls and decorations are used to create spaces (for example the children’s section). Then again, perhaps this only reflects my personal opinion about white walls being inherently uncosy, it seems to be a ”neutral” standard in apartments as well and I’ve rented plenty of places where the walls had to be covered in posters and photos to combat the eerie feeling of being lost in a desolate snowstorm. Either way, the colours of Blackpool were wondrous and if I remember correctly the decorations had been made by a local artist (maybe even a former staff member?) and the imaginative bookcase seems to have been built by local dads.

- Bookshelf in the children’s section.

- Dads in focus at Blackpool Central Library.

Supporting dads through collaboration with the charity Dads Matter UK was an interesting focus that I haven’t really noticed in libraries before (maybe I’m just unobservant) and it made me think about libraries as an important place for such activities. Libraries are neutral and open spaces and even if you go their for peer support groups to help with your anxiety etc. no one seeing you at the library would immediately know the purpose for your visit – you might just as well be there to print documents, get books with your children, or use the bathroom. The broad scope of library activities (and activities taking place in the library) by design helps protect the privacy of the individual who participates.

- What you see when you enter Blackpool Central Library.

- Stained glass windows in Blackpool Central Library.

- An exhibition display from a previous event.

My usual library tourism is just popping in at the public library in the place I’m visiting and have a look around. If no people are around I might take some pictures and I’m a fan of studying the event boards to see what kind of activities libraries and their partners (for example local organisations) arrange. Sometimes friendly library staff ask if I want any help and sometimes this will lead to a short conversation about me being a librarian and that I like visiting libraries whenever I travel somewhere. In Blackpool I started talking to librarian Jools who prompted by my story started sharing facts about the library and the town. Unfortunately, I got to the library just 15 minutes before closing time on September 28 so we didn’t have much time, but Jools kindly invited me back the next day to see the upper floor and to hear more about the library’s activities.

- Stained glass window: Stories

- Stained glass window: Reflect

- Stained glass window: Imagine

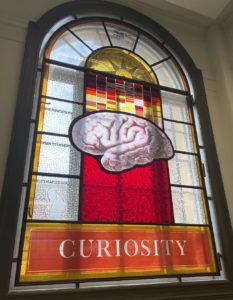

- Stained glass window: Curiosity

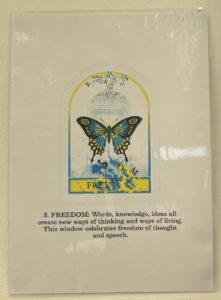

One remarkable feature of the library is the stained glass windows that were made for the library’s centenary in 2011. They were created through consultation with community and staff members and the themes of the windows reflects Blackpool’s history, present, and future. By each window there was a sign explaining the window and I’ve included an image of the Freedom window explanation in this post (the text: FREEDOM: Words, knowledge, ideas all create new ways of thinking and ways of living. This window celebrates freedom of thought and speech.) I’m sure anyone familiar with me or my research can imagine how much this resonates with me. You can read more about the centenary redesign of the library here, or the making of the stained glass windows here.

- Colours for adults as well! An autumnal book display.

- Anyone up for banter, brew, and biscuits?

- Stained glass window explanation: Freedom

The library also offers a lot of activities to support its community’s social, reading, and IT skills needs – among other things (see image of the event board to explore further). When I met Jools the next morning she had just broadcasted a digital story event through the library’s social media. Here’s an example of a digital story session on Blackpool Libraries’ facebook page, and below is an image of the studio which was a corner of her office. I’ve understood (not just based on Blackpool) that in many public libraries digital events have started and/or expanded during the pandemic, and they continue to be a vital part of post-pandemic library services to make sure the library can reach all of its users.

- An improvised studio for digital stories.

There always more to say and write and tell, but I’m wrapping up this post and I hope your curiosity will lead you to this amazing library one day. Going back to my British friends who said Blackpool was a rundown resort that had seen its best days I’d have to say that whatever else in the city may lead to this impression the library certainly doesn’t. It is such an imaginative, beautiful, and friendly space and I hope and assume that Blackpool citizens share my sentiment about the library.