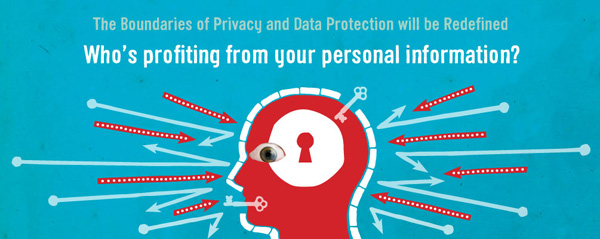

IFLA’s 2013 Trend Report is a highly insightful and useful document which in retrospect seems to be well ahead of its time. Looking back at the information landscape that year, the SDGs, the AI boom, the pandemic shift to digital education and communication, and the Cambridge Analytica scandal were yet to come. Edward Snowden’s leaked classified NSA documentation the same year, and Dr Olivier Crepin-Leblond’s leading statement (see below) in the insights document was not common knowledge, I think, among librarians:

Data collection today is not constrained to the Internet: it is present in every action in the “real” world too, from shopping to travelling, working, etc…if this is left to Technology, we have passed the point of no return: today it is technically possible to follow someone in their daily life simply with image recognition, their mobile phone, their credit card and their Internet use.

There was an extensive literature review, expert submissions representing a broad range of experts (a wide variety of NGOs, academia, industry…), and a thorough process of meetings and debates to discuss and develop approaches to the trends. I attended a workshop about the trend report at the BOBCATSSS student conference in Lyon in 2016, which I apparently also wrote about (I honestly have no memory of this, but it was two weeks before I moved from being an MA student in London to become a policy and advocacy assistant in The Hague, so maybe I offered? I was looking for the original BOBCATSSS 2016 web page but the domain seems to have been overtaken by some marketing business bent on preying on library nostalgists like me). Btw I was attending the conference to give a badass workshop on EU copyright reform. B) Light blue colour on text to make me seem more humble, hehe…

”Who’s profiting from your personal data?”, CC BY 4.0 IFLA

In short, it was good work. Built on facts and dialogue. The insights document is still used in information studies courses to teach future librarians. It was part of the curriculum in a course I taught at Åbo Akademi University in the autumn 2021 and it gave me many ideas on how to take the discussion further. One of the course assignments was to discover and present new trends – or rather updated trends with a national policy twist – relating to the original document. This inspired great ideas and discussions in the class room and I got a really positive vibe about the future of librarianship (to be fair, interacting with students will almost always spark joy as they have not yet found themselves locked in the working adult’s mantra of ”avoiding and accepting things” (sv. förhålla sig till och finna sig i saker) but continuously question the order of the world and take innovative approaches to solving its problems).

While the original document was built on facts and dialogue, the 2022 update (subtitled A call for radical hope across our field) seems to build its narrative on emotions and anecdotal evidence. Shying away from the broader perspective of a global information society it seeks to present ”ideas for how we – as a field and as a federation – can make ourselves ready not just to face, but to make the best of the future”. A pep talk document? The document has been co-written by IFLA’s emerging global leaders, i.e. a group of young library professionals who (as far as I understand) were appointed leaders by receiving WLIC conference grants in 2022.

Who are and who were the international library leaders?

I think this new IFLA approach to international library leadership is quite interesting. Some might remember the IFLA International Leadership Programme, ILP, (you might notice I’m using an Internet Archive Wayback Machine link – it’s surprisingly difficult to find any information about ILP on the new IFLA website – the old links are dead and if something still can be found on the webpage it’s not through the site’s search function which clearly was not made by a librarian), which was a ”two-year Programme designed to increase the cohort of leaders who can effectively represent the wider library sector in the international arena, and to develop leaders within IFLA.” This programme was developed and initially led by the amazing Fiona Bradley, with the second round skilfully led by the current acting secretary general Helen Mandl, and its

”activities may require the participant to undertake a number of tasks including: evidence-based/secondary/comparative research; writing documents such as policies, submissions, interventions, statements, speeches; liaison with other bodies at national, regional or international levels; representing IFLA at international or regional forums…”

The associates for the programme were required to have some seniority in their leadership experience (”It is expected that participants will already have demonstrated their leadership within IFLA and/or a national or regional association that is a member of IFLA”). I’m not sure why this programme was discontinued and why international library leadership now seems to focus on new talents who will be ”the leaders of tomorrow”, but I do think it has an impact of what you can bring to the table when updating one of the most visionary and insightful documents IFLA has produced. I mean, I am young (34 thanks for asking) and quite brilliant, but I’m no Divina Frau-Meigs (… and that’s about as humble as I’ll get).

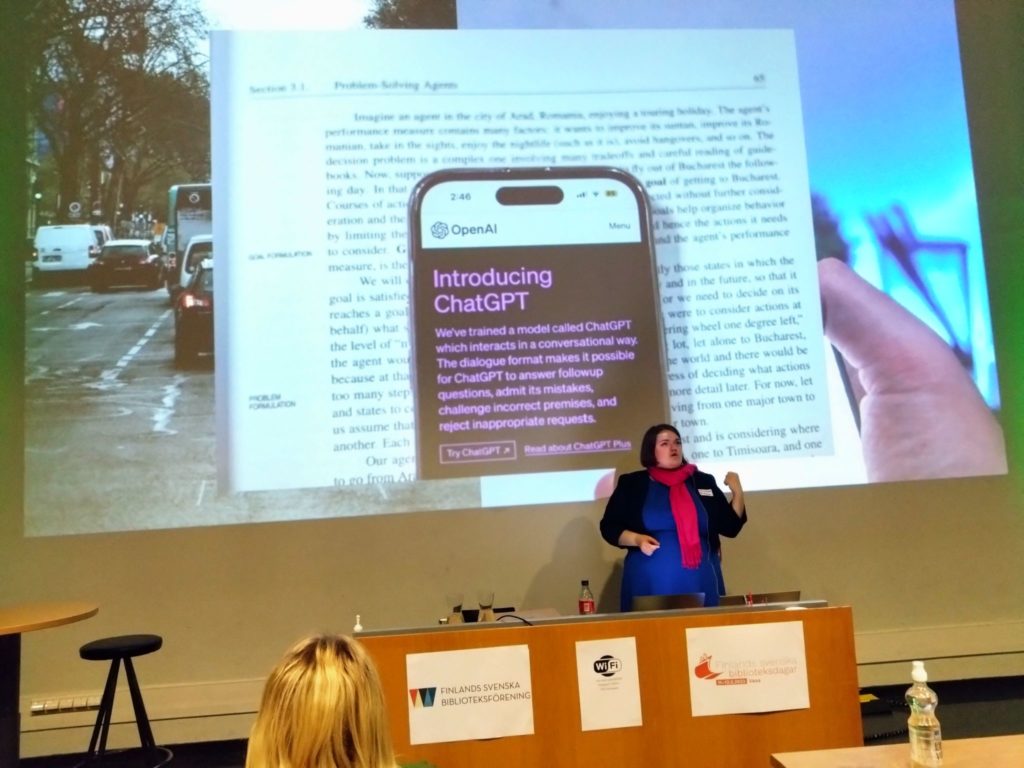

Self-agency and global action – important building stone or distraction from target?

I think the lack of experience and inspirational aspiration might be the explanations for the content of the 2022 update. Obviously, I do not take issue with the thoughts of the emerging leaders – my criticism is toward the decision to use this particular publication as a feel-good pamphlet for IFLA’s bizarrely abstract strategy (we all have different interests and I happen to think that a library related strategy document in the 2020s that mentions neither ”information society”, ”copyright”, ”AI”, ”privacy”, nor ”open science” is a bit removed from reality).

In the 2022 update ”the ideas shared have been structured according to the four pillars of IFLA’s mission – to inspire, engage, enable and connect the global library field.” Building on these pillars, the update presents ”our own to-do list in the coming years if we are to be ready to seize the opportunities and face down the threats that lie out there for us.” Here is a summary for The recommendations for our field, and I have taken the liberty of emphasising some of the words:

1. We need to see libraries as players in a wide variety of policy areas

2. We should be more open in where and how we engage in advocacy, making a wider variety of issues our own

3. We should intensify and improve our own advocacy

4. We need to adopt a broad definition of our field, and ensure that being part of it is synonymous with action

5. We must see outreach as key to achieving our missions

6. We need to feel a sense of agency in the face of the future

7. We need to embrace and share innovation

8. We need to see ourselves as a core part of the education infrastructure

9. We need to support emerging leaders as a core plank of sustainability, while also seeing that we all have potential to develop

10. We must make connecting with others in our field an integral part of our practice

11. We should invest seriously in our connections with partners and supporters

What I’ve emphasised are wordings that I interpret as related to some kind of inner development for the individual librarian (maybe also the organisation). To take action in the world, we need to take action with ourselves first. This is a very interesting rhetoric that I also recognise in the Inner Development Goals, a set of goals created because someone realised that the reason the progress of the SDGs is so slow is because ”we lack the inner capacity to deal with our increasingly complex environment and challenges. Fortunately, modern research shows that the inner abilities we now all need can be developed.” The IDGs lists skills we need to drive this change, for example ”a commitment and ability to act with sincerity, honesty and integrity”, ”skills in inspiring and mobilizing others to engage in shared purposes”, and ”willingness and competence to embrace diversity and include people and collectives with different views and backgrounds”.

Why are strategy documents moving in this emotive direction? Is it related to the post-truth society, misinformation, and lack of trust, meaning that the ground for trust and collaboration we now have to build on is not a common mission (e.g. ”reform copyright!”, ”literacy for all!”) but a common sentiment (e.g. ”we feel knowledge should be accessible to all”, ”we feel we should be open to new innovations”)? Either way I think it’s safe to say the set of recommendations are far removed from the questions asked in the initial trend report, compare for instance ”We need to embrace and share innovation”, ”We need to feel a sense of agency in the face of the future” with ”Who will benefit most from the changing information chain? And how will our regulatory frameworks adapt to support an evolving information chain in the new global economy?”

Quo vadis, IFLA?

There is also a list with recommendations for the federation. A main problem for me is that many of these recommendations are so vague that they are hopeless to take action on (” We need to make links between global issues and individual experience”; ”We should understand our field and its needs and how to support it most effectively”).

I had originally copied and commented a lot of text from the 2022 update because there is a lot to comment on. I even made a new subheading: ”An idea store for the Newcomers Session”. But I felt it was a bit useless to comment on specific paragraphs because I do see what this document (as a whole) is trying to do. I don’t fully understand its purpose but I do see how some people could be inspired by it.

What I don’t see is how it can be so far from the original document, and how it doesn’t relate to trends and the trend report at all (unless we count inner development or being inspired as trends). Only if you squint you can see some relevant highlights in the 41 pages long text. For example on pages 25 and 34, where the open movement, urban development and public health are discussed in some (small) detail. The original trend report is not referred to but one could make the connection.

Interestingly the document ends with ”this report is all about the steps we can take in order to build a sustainable future for our field”, cementing that this trend report and maybe even IFLA’s work in general, is mainly about our field. Ironically it then ”calls on readers to think outside of the box” – I suppose it means outside the box, but not outside the books? Pun intended.

The end

Actually, it doesn’t end there. The last few paragraphs are inexplicably dedicated to an assessment model you can apply to your national library field: ”You could start by looking at them individually and assigning a score, before having a group discussion where you compare assessments…” I wouldn’t say such evaluation methodologies are a particularly good example of out-of-the-box thinking, but sure, I guess it is a way to put numbers on a text that has been heavily dependent on feelings and impressions.

”Multiplying the scores by the weightings would make it possible to come up with an index of sustainability, which in turn would make it possible to identify in which areas you could be focusing effort in order to boost your overall performance.”

An index of sustainability.

At this point I’m just speechless.