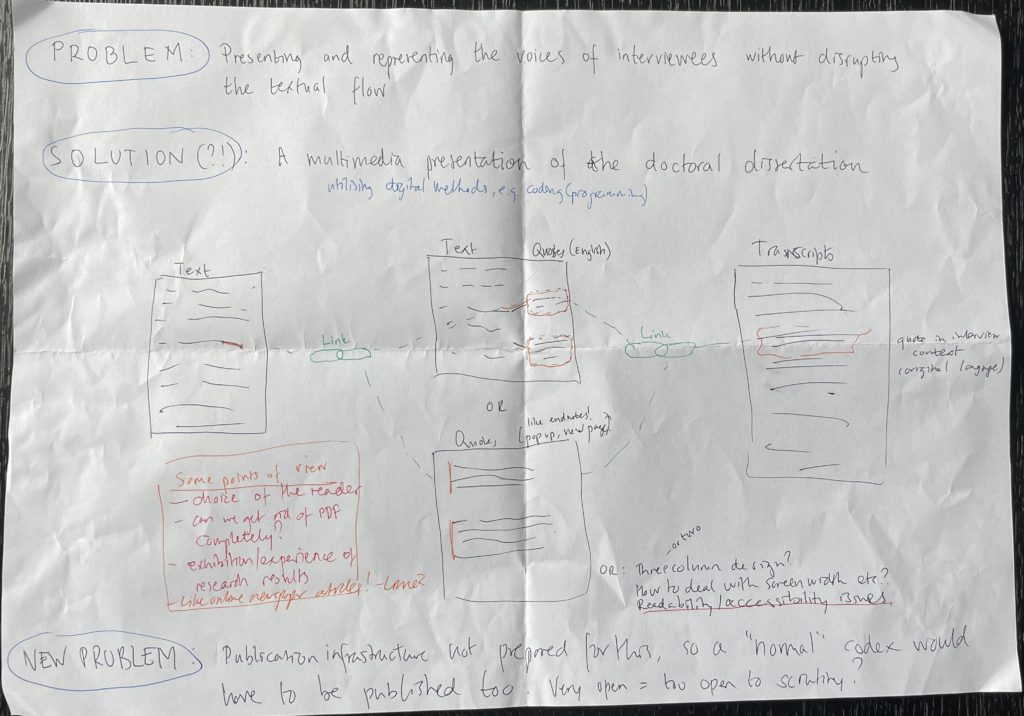

While looking for something else I found these pictures of when I visited Vyborg in 2013. I went there on a group trip with Östra Finlands nation (my student nation’s friend nation in Helsinki) since their old province was the easternmost parts of Finland, including Viipuri – Finland’s second city until they lost it in 1944. I could go on (oh I really could) about how fascinating the city and its history is, but I will instead focus on the most important part – the Vyborg Library.

Vyborg Library designed by Alvar Aalto. Ninaraas, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The reason I’m resorting to an image from the commons is that the library was being renovated when I was in Vyborg. And with the current political situation it’s unlikely I will be able to visit the library anytime soon. Very sad, as I’m very fond of Alvar Aalto’s library architecture. The light!

| Library | Vyborg Library |

|---|---|

| Place | Vyborg, Russia |

| Coordinates | 60.709006, 28.747302 |

So, when I was there, this is what I could see of the library:

- Restoration of Vyborg Library in 2013, 1. (And umarej…?)

- Restoration of Vyborg Library in 2013, 2

- Restoration of Vyborg Library in 2013, 3

Not post card worthy I’m afraid, but I’m still glad I went there and had a look, and I can say I’ve been there and made my best effort to see it. The restoration was a join project between Russia and Finland, just like the restoration of Saimaa canal (that was also the route we took – from Lappeenranta to Vyborg). While I recognise that the international name is the Russian Vyborg (far be it from to cross UNGEGN) it does hurt not to use Viipuri (or the Swedish Viborg).

I think I mentioned this in the Lappeenranta post a few months back: their local history museum was surprisingly focussed on telling the story of Viipuri, the capital of Karelia, and was dominated by a large model of Viipuri, with a main piece obviously being the famous castle depicted below. The emotional connection to Viipuri, and how hard the loss was, is very apparent in Finland.

Vyborg Castle.

A Finnish speaking student nation in Helsinki (in contrast with the previously mentioned Östra Finlands nation, that is Swedish speaking), Wiipurilainen osakunta, celebrates the Viborg Bang (that’s a Wikipedia translation, in Swedish it’s Viborgska smällen and Finnish Viipurin pamaus) on 30 November every year to commemorate when Knut Posse blew up the castle to defeat the Russians in 1495. It’s a good party! The bang is also included in the Carta Marina.

Another fascinating thing in Vyborg was the sudden appearance of the Uppsala skyline on a public transportation bus! My V-Dala librarian colleage Nina instantly recognised it as the look of the old city buses in Uppsala.

Uppsala silhouette in Vyborg

I’ve done some research on this and it turns out these old buses were gifted from Uppsala to Vyborg some time in the 1990s, and apparently they never repainted them. A nice surprise and a piece of home in a faraway foreign city. But then again, Vyborg has historically been a very cosmopolitan city. Kieli vieras taikka tuttu, as it goes in the classic song Sellanen ol’ Viipuri.

It’s one of my favourite songs, and an absolute banger to do at a karaoke bar when there are older Finnish people present (sorry but young people are clueless – I’m an old soul). I’m quite partial to this chaotic rendition, but below I’ve embedded a cleaner recording, hehe:

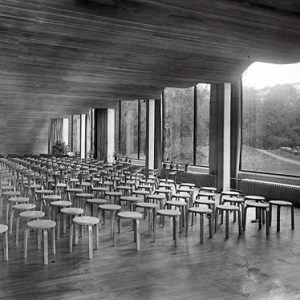

Yes, ok, so not much library content here – for obvious reasons. But please enjoy these pictures of the library auditorium from the 1930s and 2014 respectively. Just look at the Stool 60s lined up!!! If you don’t feel anything in your heart when you see that, I’m afraid you neither have a heart nor an appreciation of art.

- Vyborg library auditorium, 1930s. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Vyborg library auditorium, 2014. Ninaraas, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

(Links to the auditorium pictures because I can’t seem to put them in the gallery image texts: 1930s and 2014.)